Something came up in coaching this evening that I thought I would write up into a blog post: the Power-Technique Feedback Cycle.

This has been part of my way of thinking about and teaching complex movements which is almost intuitive, and I thought might be useful to write down and share.

Introduction

What I’m talking about here is the way that a complex movement — ie anything more than just 1 thing — is made up of a number of moments of “power” and technique, and that these need to work in symphony, and how this is part of the learning and development journey of a particular movement.

I’m using the word “power” in a simplistic and technically incorrect way here; we could be more nuanced and differentiate between power and momentum and energy, but to explain this interaction and cycle easily, I’m just going to lump it all together as “power”. Muscles doing work stuff.

For technique, I mean movement pattern(s), certain alignments of the body or a coordinated sequence of movements of various body parts in harmony. Of course this inevitably has some “power” in it because there are muscles etc moving the body into various positions, but let’s just group those little (important) adjustments into “technique”.

In a simple movement, such as a two-footed box jump, there is simple power and technique. You put power in with your leg muscles pushing, and there’s some technique to control that power, primarily in how you angle it: straight upwards into the air or forwards to land on top of something. That’s the sort of thing I mean as a “simple movement”, and complex movements are made up of lots of little segments of this.

Explaining the Concept

That was actually a simplification. If we look closer at the movement, it actually contains a whole system and pattern of power-technique interactions. Crouch down, chest forward, arms back, to get into the start position: that is all technique. (Or perhaps you are doing it dynamically with a small moment of plyometric at the bottom to bounce from crouch and arms back to springing forwards — in which case there is power in there too!). Then the arms swing forward and the chest rises — power. The correct movement of the chest — technique — brings this energy upwards to help with some lift (somehow? I don’t think I fully understand what the arms do in a box jump) — and there is a synchronicity with this arms-chest movement that rolls the body forwards over the feet, creating the right angle through the foot to roll onto the balls of the feet — technique — to allow optimum power to be generated from the leg muscles as they push off. This is then the output as you lift into the air!

And that is the idea of the power-technique cycle that I wanted to share!

And then that “power” (momentum) is in the air, whereupon you need both technique and “power” (energy, or at least, work done) to absorb the jump into a landing. If you have bad technique, even a strong-muscled person will slip on the landing and smash their shins/face/heels/whatever. If you have good technique but not enough “power” in your landing, you will injure something and do some sort of damage to your body.

Analysing some Movements

Being able to break a complex movement down into the moments of power and technique, and the different segments of a movement, is crucial for being able to teach it and give feedback to someone else. It also helps for getting better yourself, especially if you are filming for some self-analysis, but actually intuitively you will usually figure most of it out yourself.

Wall run

First phase is the run-up. There’s a bit of technique in how to run, so I wrote that in small, but mostly this is about giving us some power to enter the movement with.

Then there’s the take-off. The input “power” comes from the momentum from the run-up, which has to be controlled and directed with technique, plus the extra push on take-off, which also has to be in harmony with the technique. If the technique of the take-off isn’t good, then they go splat into a wall.

The output from the take-off takes the person through the air, at a good trajectory if their technique was good, sailing nicely upwards and with good energy to take into the wall if their power was good. This “power” (momentum) is in the body as the athlete comes into contact with the wall. Now, we need good technique on the foot on the wall: the right height, the right part of the foot. Too low and it slips down; too high and it pushes backwards not upwards; a failure in technique here affects power output. If the technique is good, then that allows a transfer of the momentum to go upwards, which is a “power” output of this segment, plus the additional power of the push into the wall to add to this.

The output is the upwards momentum, or “power” in the simplistic explanation.

Teaching in Segments

Breaking it down into these segments helps us to learn these different things. When I teach, I sometimes teach systematically, isolating each segment to get the technique right so it can be learned in isolation. Usually I focus on the wall foot at a low power, at walking speed, until the athlete is able to get some push, because their foot doesn’t slip and the position is right that they can push through it. This is refined into an upwards output.

If at any stage you change any part of it, you usually have to change other parts too! It’s a complex system with interactions, not distinct things. So, once someone adds more power, the movement pattern of the technique has to be different.

As the wall foot push technique is learned, we can start to add more power on the take-off. The athlete can then iteratively develop having their foot a bit higher, engaging it more to absorb and redirect, and perhaps also using their other leg to help drive up and control this power.

Then we focus on the technique of the take-off, adjusting take-off foot distance so that they aren’t too close or too far from the wall, to get a good trajectory going upwards into the wall-foot.

Changing the technique of the take-off means you get more power output, so the technique of the wall-foot has to change too.

And then, once they have a good take-off technique, you can add more power (momentum, speed) in the run-up. This will translate to more power in the output at the end of the movement, up the wall. But if someone tries to learn a wall-run with too much run-up, it is much harder because the technique isn’t developed enough to handle! That’s more power than they can control.

This systematic, segmented way is the most effective way to teach, I think, and for most movements I teach I have developed this sort of layered segments. I don’t always use this though: it’s best for a focused athlete, but it is less engaging for someone with less focus, like most children. Starting at walking speed is less fun. They want to be able to “do” something very quickly, so I usually set a version that they can almost already do, and then only after that work on refining technique.

Tic-Tac

The tic-tac is pretty similar to a wall-run!

You have the run-up, which requires the power + technique combination of running, but also the technique of the approach angle for the wall (usually diagonal).

Then there’s the take-off, power of the leg pushing plus technique to control it and balance the rest of the body and bringing the other leg through.

Then there’s the step on the wall, which requires technique to be in the right place, power to absorb and push, and technique to do a good, controlled push. This latter bit is the crux of this movement, the technique of pushing off the wall!

For a good tic-tac, the athlete should push up-and-away from the wall to get a good arc trajectory, and use their other knee to drive up into the air. It’s a similar movement to the “open the gate” hip opening exercise, if you know that, footballers use it a lot. Really, this is integrated into the push off the wall to be the core movement pattern of the tic-tac, but when teaching I usually add this as a layer afterwards, so that only after they are comfortably pushing off the wall, controlling it, and landing safely (!) do I explain how to do the best push off the wall.

And leg strength goes with this technique to get the most output “power”, which sends the athlete floating and flying up into the air, through the air, before landing. If their technique was bad, they are out of control, and might twist an ankle or knee on landing. (Beginners can easily hurt themselves learning tic-tacs if they don’t have enough control, because the feet often turn to the side so the foot-leg-hip alignment doesn’t match the direction of travel.) Or, a seasoned athlete aiming for a precision landing on something might slip off.

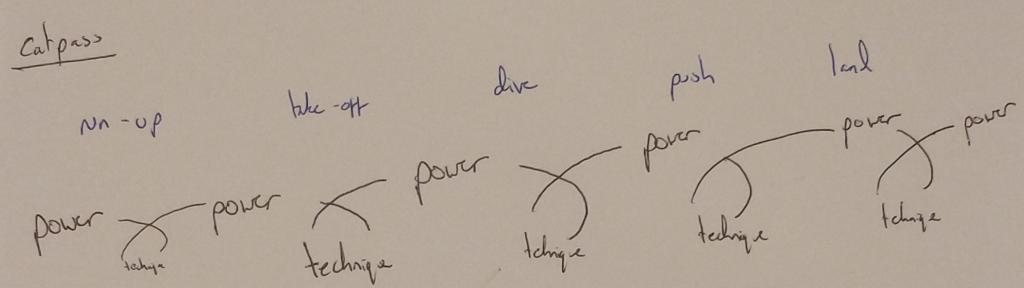

Cat-Pass

The catpass is a complex movement, probably one of the most complex “single” movements in our parkour movement vocabulary. The athlete runs forward, executes a technical take-off to angle forwards (ideally in most cases a split-foot take-off), dives in an arc through the air (shoulders forwards, hips up), catches themselves on both hands, pushing and timing it right to contract the core and have the hips rotate again compared to the shoulders, release the hands, land (without clipping feet on the obstacle and having rotated enough).

The segments are difficult, and the systematic learning process has many more stages than other movements.

I won’t do a complete breakdown or guide, because by now I think you understand the concept of power and technique feedback cycles. But to mention a few parts.

The take-off has to have a good technique and timing of leaning forwards for the power to be useful. Especially if you want the run-up momentum to be taken on.

The dive forward is technical, dive forwards with the hips rising, making an “angry cat” style arc with the body, like a big cat going for a diving pounce. The athlete can only commit the power to this if they already have the technique to deal with it at the next stage (or, everything is soft and the landing doesn’t matter!). You can’t do much of a dive if you don’t know how to use the arms. Again, without good technique, there isn’t power going into the vault.

The push-through has a complex moment of power in the push with a bit of blocking for the body to contract and rotate to fit through.

When I teach this, I usually cover a basic version that teaches the technique for the take-off, like an upwards monkey sort of vault, then add an exercise to teach them how to get their hips high, and what it feels like when they do. Then I do add exercises for the dive and for the push, and explain how these three parts have to work together in harmony. The movement at this stage is only partial, usually “landing” on top of an obstacle (by using a long vault block) so that it doesn’t need full control and there isn’t a post-vault landing to deal with. The exit can be practiced by starting on top of something as a ‘level dive catpass’ sort of thing. Then, when they are able to do all the component techniques in each segment and have adequate power, and have the right confidence, they can put it all together.

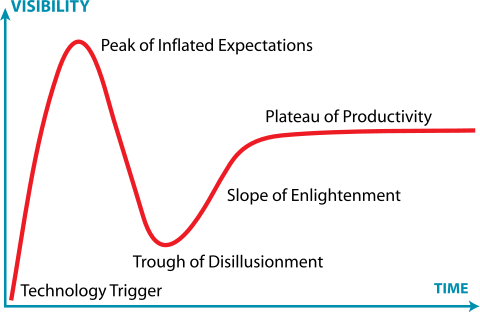

Positive and Negative Learning Feedback Loops

Some movements have a positive feedback loop when learning them, making them easy to teach and learn. Some have a negative one.

In a positive loop, as the technique gets better, it becomes easier to get more power, which in turn makes the technique better, and so on. It’s fun and easy to learn. A tic-tac is mostly like this: start with basic power, then add one bit of technique. Yay, you left a wall with power! Now change this technique. See, more power! Fun! Progress! Now chance this technique! Yay. Some vaults are like this too. A step-vault, for example, can be done slowly to learn all the technique, then power can be added, and it’s a positive interaction. You could also start with power and a modified technique (like going completely over without any or much step), and then add in the technique.

Some movements, however, have a negative feedback loop in the learning of the movement. This means the technique doesn’t really make sense, not clicking, or even actively hinders, and may also be dangerous, until there is enough power. In this, the technique only works with more power, but you can’t do more power without the technique!

The catpass is like this. There certainly isn’t usually a positive feedback loop. You can’t do a big dive until you have good take-off power, but you can’t do a good take-off until you have the technique for how to dive and push. If you don’t do a good dive, the risk of smashing knees or clipping feet is high, so you can’t get much power. But without much power, how do you do a dive technique? You can’t dive until you know how to handle the dive with the push-phase, but you can only do a meaningful push when you are diving into it… Which is why I described teaching it by teaching the different segments separately (so that each segment can have a positive loop), until they are ready to be integrated together into the whole movement.

Another common example of a negative feedback loop is the traditional parkour roll. If you focus on technique without power and do it slowly, the movement doesn’t really work, because it crumbles. A beginner who is taught how to go into a diagonal shoulder roll will then crumble in the middle, because without power the roll doesn’t actually… roll. Unless the person does work in the middle to make themselves a ball and create the structure. But if you do it fast, with enough power to roll, they won’t have the technique to handle it, and will usually smash their shoulder or roll on their neck, or just bail as their safety instinct takes over!

Which is also why I teach rolls in a totally different way, either starting from the middle (lie on your back, make a ball, roll around, etc) or starting with a different movement, the sideways roll, to teach roll technique, before than transitioning from a sideways roll into a forwards-diagonal parkour shoulder roll.

Really, I suspect that all movement learning cycles have both negative and positive phases. For a basic box jump, most people have the pre-requisite power and technique that it is a positive cycle. But someone with very little leg muscle — perhaps it’s atrophied — or limited technique — perhaps a movement limiting condition such as dyspraxia or cerebal palsy — would be in the negative feedback loop phase. They can’t generate power because their technique isn’t good enough and they are always out of alignment, or they don’t have enough power that their technique doesn’t make any sense or has to be modified. But for simplicity, for the “average” athlete, or the “average” ability an athlete has when learning a move, most moves will be one or the other.

(And you could also throw the skill development cycle into this movement feedback loop development, because a complex movement will have moments positive and negative feedback loops throughout the multi-stage development cycle. But that’s getting a bit too much to go into detail on… just floating the idea.)